REVOLUTIONARY EXILE: SIDNEY SOKHONA

REVOLUTIONARY EXILE: SIDNEY SOKHONA

Film Programme

Sidney Sokhona’s NATIONALITÉ: IMMIGRÉ and SAFRANA (OR, THE RIGHT TO SPEAK) should constitute 11th-hour addendums to the canon of post-colonial Francophone cinema. Made when Sokhona was in his early 20s, recoiling from a rash of exploitations and abuses in France’s African migrant community, the films form a blistering duo: NATIONALITÉ: IMMIGRÉ dramatizes the real-life rent strike undertaken by Sokhona and his neighbors in the Rue Riquet settlement housing, a “docu-fiction” of its own community in collaboration that’s unlike anything you’ve before seen in “world cinema”.

Assuming the position of both French and African filmmaker, Sokhona published a kind of manifesto in Cahiers du Cinema entitled Notre Cinema (Our Cinema), wherein he decried the cultural feedback loop enabled by state funding (especially in postcolonial cases), the incessant use of African landscapes as backdrops for tawdry Western melodramas, and the pigeonholing of black movies in festival programming – citing that the 1976 Cannes Film Festival included CAR WASH in its main slate, but consigned Ousmane Sembene’s CEDDO to competition in Directors’ Fortnight. If SAFRANA closes on an impossibly optimistic note for Sokhona (as the audience has, over the too-brief course of two movies, come to understand him), it reveals itself in hindsight as a byproduct of the French example, wherein the the organizing onscreen bears a utopian fruit that’s nevertheless untrustworthy. (Sokhona alleges that audiences were far more skeptical about the immigrants’ warm countryside reception in discussions following screenings in Paris.) What’s universalized in the humiliations of NATIONALITÉ: IMMIGRÉ remains – or as Sokhona put it to Cahiers, “Immigration has not only served to alienate us but also to teach us to be ashamed of what we were before. Any immigrant with a conscience realizes he has as much to claim on the workers’ side as the farmers’, today.”

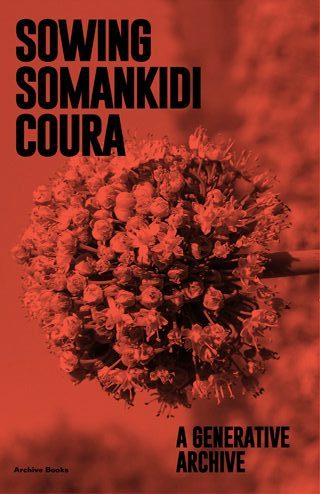

A consortium of West African immigrants would band together in Paris to form the Cultural Association of African Workers in France (ACTAF), an organization in solidarity with liberation struggles in former Portuguese colonies. ACTAF would become the Somankidi collective, making a healthier living off the farming practices depicted in SAFRANA – making it a sequel both political and socioeconomic to Sokhona’s first film. The laborers relocated to the Senegal river, where they remain today; founding member (and SAFRANA star/participant) Bouba Touré would later tell multidisciplinary artist Raphaël Grisey that Somankidi Coura was founded “because we didn’t want our brothers, our cousins, to come sell their labor in France.” To see 8mm images from the cooperative’s founding – vibrant young African men in snappy duds, at once relaxing and working together on a shared cane harvest – is to reckon with their post-postcolonial power. Grisey’s split panel documentary COOPERATIVE observes the ongoing collective in juxtaposition with the village’s Parisian roots of origin, whereas BOUBA TOURE, 58 RUE TROUSSEAU, 75011 PARIS FRANCE allows its namesake to contextualize the political struggles of the time (including a tacit, unignorable Pan-Africanism) while surveying the walls of his apartment in Paris.

As the Somankidi Coura celebrated its 40th anniversary this past January (complete with an exhibition of Bouba Touré’s photographs), Spectacle is thrilled to present these rare and invaluable films in their first-ever New York City screenings.

This series is made possible solely thanks to the collaboration of Raphaël Grisey, Tobias Hering of Kino Arsenal, Cinémathèque Afrique/Institut Français, and Amélie Garin-Davet of the Cultural Services of the French Embassy.